Activism and

the Power of

Digital Media

youthforchange.org

Tech Habits

Everyone

Should Have

lifehacker.com

Digital Media

May Change

the Way

You Think

natureworldnews.com

reasons for

Digital Youth

Participation

euthproject.eu

teenagers

can realise

their inner

activist

developmenteducation.ie

activism in

repressive

environments

mobilisationlab.org

Marketing

isn't that

Complex

digitalmarketingmagazine.co.uk

and the Power

of Digital Media

youthforchange.org

By Activists

mashable.com

reset.org

of Digital Tech

meta-activism.org

Giving Power

To Youth Activists

theodysseyonline.com

New Political Practices

booksandideas.net

europanostra.org

Competition

ec.europa.eu

ec.europa.eu

eu-youthaward.org

ec.europa.eu

europarl.europa.eu

Youth, Activism and the Power of Digital Media

As more and more young people find themselves drawn to the world’s issues, the question of how to go about addressing them becomes increasingly important. One area that has proved to be particularly contentious is that of digital media. While there are plenty of arguments for the use of social and online platforms, there have also been various attacks on the efficiency of online activism.In particular, many have debated the subject of “slacktivism” – the idea that most online activism is ineffective because of the limited commitment it takes to share media, sign a petition or post material. This article will highlight why this is an important issue for young people, how online media can be used for activism and the pros and cons of doing so.

How young people use the internet as an activism tool?

Young people are in a prime position to use technology and the internet as a tool – many of us have grown up with various forms of technology in the home and at school, we understand how to use social media to our advantage and the internet isn’t new or intimidating to us.This isn’t to say that the older generation aren’t able to do the same things or even better - but for most young people, using several kinds of digital media on a daily basis has just become another aspect of our lives. Even the most skilled adult users have still had to adjust from a time before this became the norm.

When it comes to activism, we can quickly reach more people than ever before in a variety of different ways. From lower levels of action such as signing petitions or sharing an article to more time-consuming efforts like posting a blog or video, activists have an array of tools at their disposal. Spreading awareness and organising gatherings or events no longer has to take up a lot of time and resources, meaning these can be directed elsewhere.

Educational resources in the form of articles and videos are plentiful and often thorough (a good example is that of Laci Green, a feminist YouTuber who frequently creates videos covering gender issues, sex positivity and self-care). These platforms are useful for all activists in both self-education and posting our own media to help others.

'Slacktivism'?: the pros and cons of online activism

However, like all systems, there are of course limitations to online activism and some of its best qualities are also its worst. As anyone can post anything, not everything is properly researched, which can lead to a potential spread of misinformation, and even those that are produced carefully can suffer from hateful trolls among more positive commenters. (See our video below for a few ways to stay smart online).Since the ALS Ice Bucket challenge and Kony 2012, there has been a lot of debate about whether online activism is even worth pursuing at all. Many lower level forms are dismissed as “clicktivism” or “slacktivism”, insinuating that there’s no real effect and that the use of online media is a fad that merely makes people feel good about themselves.

While this could apply to less effective actions such as changing your profile picture to show support or liking a post about an issue, I still think it’s somewhat misguided. I’m not sure people who do just these things consider themselves activists or get any great sense of philanthropy – we like things because we like them, not because the act of clicking a little blue hand is going to change the world.

Other higher level forms of activism, such as signing petitions, sharing media and asking others to donate to a cause (especially when you’ve already donated yourself) don’t deserve this ruthless dismissal. While they take just seconds to carry out, their full effect can be staggering. Petitions have existed for centuries, but websites like change.org have made the process far more straightforward and much quicker. Even if the petition itself doesn’t achieve the desired change, it will have taken less time and effort than a petition that took weeks to collect by hand that received the same result.

Sharing media can raise awareness, educate and motivate great numbers of people in ways that can’t be measured – there’s no knowing how many people might be deeply affected or who might be spurred into a lifetime of action from one person making a particular issue known to them.

Donations are also easier and safer online for both charitable worker and donor – people may be reluctant to give money on the high-street and collectors have to stand and be rejected for hours, but online the process is secure, quick and easily shared with others. And clearly, economic support makes a very substantial difference to those ultimately benefiting from it.

Opening up new channels for change

Those criticising online media often tell users to step away from the computer and go out to volunteer or donate, ignoring the fact that not everyone has lots of money to donate or time to spare, even if they care about the cause deeply. In addition to the points mentioned above regarding donation, online media can allow people to donate as little or as much as they feel able. Digital activism allows those with little time or spare cash a chance to participate in a cause they care about, without putting undue pressure on themselves. Causes are important, but self-care is too – activists can’t help anyone if they’re overly stressed or fatigued from trying to do too much.Saying “step away” also indirectly dismisses those who are actually donating and volunteering offline, but are using additional platforms to reach a wider audience in more efficient ways. Online activism often goes hand in hand with physical activism, as real passion for a cause leads us to find as many ways to help as we can. It also allows people who want to support multiple causes the chance to help each on different levels (for example, I care about gender-based violence, LGBT+ issues and animal rights, but much of my time goes into the first one – online activism allows me to support the other two as well).

Not everyone can - or should - be an activist

Finally, not everyone has to be an activist. Obviously, improving the world would be a lot faster and easier if every single person wanted to spend their lives working on an issue. But not everyone does and that’s completely fine (probably better than fine, there would be chaos if everyone upped and left their day jobs!). Activism should be pursued out of passion and determination, not guilt.Youth in particular are already facing unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression from mounting pressure in social and educational spheres. Adding more onto that by saying “Oh, and you have to save the world too” can only end badly. Digital activism, on any level, has allowed us to shed the mentality that we’re just individuals who can’t have any real effect because the world and these issues are just too big.

Activism at its core has always been about bringing people together, knowing that a thousand voices together can achieve great things. Even if a person doesn’t want to spend their days actively fighting for a cause, they do a lot more by clicking “share” than doing nothing at all.

While there are a few downsides to the internet in general, the use of digital media can be immensely rewarding. No one is saying that online activism should replace physical activism and as long as we’re careful, the internet can be an endlessly useful tool to support the first-hand work that is already happening.

To dismiss online activism entirely is to dismiss one of the most vital and ever-improving instruments for change that we have in the modern day.

Source: www.youthforchange.org

“Digital Youthquake” project exports digital intelligence and creativity

by Beata Lavrinoviča · October 25, 2016From 8-16th of October one more youth exchange project has been organized in capital city of Serbia, Belgrade within a field of digital communication and content creation. Youth teams organized by NGO’s from Estonia, United Kingdom, Belgium, Latvia, Albania, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia worked in groups and individually, acquiring skills necessary in this era of information in order to promote work of each NGO successfully and make it way simpler. Latvian team was represented by Alīna, Marta and Beata from Social Innovation Centre.

Project discussed functions and features of such internet communication tools as Facebook, Trello, Slack, WordPress, MailChimp, Canva etc. Participants have explored, discussed and even created by themselves own storytelling campaigns, that inspires, intrigue and promote projects shaped by them. The main idea of this project was promotion of digital intelligence and popularization of its tools within youth, as well as intercultural communication and sharing everything, that could be a source of new ideas and creativity.

Teams have not only worked on their new projects and promotion of them in social media, but also explored Belgrade and Serbian culture in general, showing great example of cross-country integration. “Digital Youthquake” project united together representatives from so different countries, and each country’s team got the opportunity to introduce its own culture and also main youth problems in their country, sharing experiences of problem-solving, as well as positive and negative campaigns. Or course, presentation of each country have been accompanied by tasting of traditional snacks, and also a lot of interesting things have been acknowledged about Balkan traditions and customs. Dancing, singing, games, movies and presentations of participants encouraged to use all kinds of creativity in creation of content in own projects.

During the activities participants have also visited a coworking space, home for NGO’s and simply youth centre “Gnezdo”, where discussion with the manager took place and project participants learned about problems of entrepreneurs and public organisations in Serbia, especially in Belgrade. The discussion revealed strengths and weaknesses of coworking spaces also in other countries of project participants, and, actually they are quite similar.

Latvian and team from other countries came back home with new creative ideas on how to improve teamwork in organisation, make it more effective and inspire young people to implement interesting ideas.

Source: Social Innovation Center

Top 10 Good Tech Habits Everyone Should Have

You’ve probably heard people tell you should back up your computer, or you should have more secure passwords. Good tech habits aren’t just for geeks—they can save you money, keep your personal information safe, and help you avoid frustration down the road. Here are ten tech habits everyone should have.10. Regularly Audit Your Privacy Settings on Social Networks

You probably already know that social networks like Facebook aren’t the poster child for privacy. Unfortunately, the only way to keep your info private—short of quitting those networks altogether—is audit your privacy settings every once in a while. Learn what each of those settings does and tweak them accordingly. You might also check out sites like AdjustYourPrivacy.com to keep up with your privacy settings on all your networks.9. Know When You’re Paying Too Much for a Product

Technology isn’t cheap, but it doesn’t have to be a complete drain on your wallet, either. There are a lot of myths out there that’ll cost you money—like buying expensive “gold plated” HDMI cables, or buying new gadgets when refurbished ones are just as good. Check out our list of money-saving tech myths for more, and never pay full price again.

8. Keep Your Desktop and Hard Drive Free of Clutter

If your desktop looks like the picture to the left, then it’s time to clean things up a bit. Not only does a cluttered desktop make things harder to find, but if you’re on a Mac, it can even slow down your computer. Once you’ve gotten that messy desktop under control, make it a habit of keeping it organized, and transfer those same ideas to the rest of your files and folders too. The easier it is to find what you’re looking for, the less time you’ll spend frustrated.7. Avoid Getting Malware (and Spreading It to Others)

We all know viruses are bad, but many of us don’t know exactly how they work—which is crucial to avoiding them. Do a little reading on what a virus is and examine the most common virus myths, then install a good, free antivirus program on your computer (and get rid of any existing viruses while you’re at it). Also, even if you aren’t getting viruses, you could still be spreading them—so watch out for that too. Photo by Justin Marty.6. Stay Safe on Public Wi-Fi

When you’re desperate for Wi-Fi, it can be tempting to connect to that open “linksys” network or the password-free network of a nearby Starbucks. However, doing so opens you up to all sorts of attacks. It sounds a little tin foil hat-y, but you really should be worried about your security. It doesn’t take any hacking experience to sniff out someone’s Facebook or other credentials, all it takes is a little evil motivation. And don’t think just because a network has a password that means it’s safe—if other users are on that network (besides you and your family members), they can access your data. Stay safe when you’re on public Wi-Fi by turning off sharing and using SSL whenever possible. Photo by °Florian.5. Be Smart About Hoaxes, Scams, and Internet Myths

The internet is rife with scams, hoaxes, and other misinformation that you probably run into all the time without realizing it. Sometimes it’s harmful—like that fake bank email that gives your identity to scammers—while other times it’s mostly harmless, like a misattributed quote going viral on Facebook. Either way, though, you should try to avoid falling victim to these hoaxes, and help stop the spread. It’s actually very easy to identify these myths online, and just as easy to avoid getting scammed. Just remember: if something seems a little dubious, it probably is.4. Know What Maintenance Your Computer Needs (and Doesn’t Need)

We all know computers take a little maintenance to run in tip top shape, but there’s no need to hand it over to some quack to get it done—most of it is easy enough to do right at home. Check out our list of maintenance tasks you need to do on Windows PCs and Macs for more info, or if your computer needs a little more help, read our guides to speeding up, cleaning up, and reviving your Windows PC, Mac, iPhone, and Android phone.3. Use Secure Passwords

Even if you think you have a secure password, you might be wrong. Yesterday’s clever tricks aren’t protecting you from today’s hackers, and you need to be extra vigilant in this age of constant security breaches. Saving your passwords in a browser is pretty insecure too—so get a good password manager like LastPass and update those passwords for the modern age.2. Back Up Your Computer

You’ve probably heard people say it a million times, and there’s a reason for it. You always think data loss won’t happen to you, but it happens to everyone one day, and having a good, up to date backup is the only way to avoid frustration down the road. Plus, setting it up is insanely easy and is something absolutely everyone can do, so you have no excuse: start backing up right now. You’ll be glad you did.1. Search Google Like a Pro

If you’ve ever wondered how us tech geeks know everything that we do, here’s our secret: we pretty much just Google everything. With the right Google skills, you can find information about nearly any tech problem you’re having, and fix it yourself without anyone else’s help. Check out our top 10 tricks for speeding up and beefing up your Google searches to become a search ninja, and avoid frustrating calls to your resident computer tech for advice.Source: lifehacker.com

UNESCO triggered debates on social media and youth radicalization in the digital age

"Protecting human rights online and offline and defending civil society and independent journalists are the solutions to solve radicalization in the long run, instead of censorship as a band-aid over the real illness," was the message delivered by Ms Rebecca MacKinnon at the workshop “Social Media and Youth Radicalization” convened by UNESCO at the 11th Internet Governance Forum, Guadalajara, Mexico, on 6 December 2016.The workshop, attended by above 80 participants, was moderated by Indrajit Banerjee, UNESCO Director for Knowledge Societies. He shared the outcome of UNESCO's Conference “Internet and the Radicalization of Youth: Preventing, Acting and Living Together”, held in Quebec City, Canada, from 30 October to 1 November 2016.

The Director said the “Call of Quebec” outcome document urged stakeholders to question radicalization narratives online, and to respond through counter-narratives and education that emphasizes critical thinking, tolerance and respect for human rights.

Guy Berger, UNESCO Director for Freedom of Expression and Media Development, pointed out the complexity of the issue of media and radicalization and presented initial findings from UNESCO's ongoing research on social media and radicalization.

The research has taken an evidence-based approach through an extensive review of diverse studies across multiple languages and regions.

It finds there is still little theorization of those complex issues of extremism, terrorism and radicalization. There is also no scientific evidence of clear causal connections between what happens on social media and the radicalization process, and the role of Internet is more of a facilitator rather than a driver of the radicalization process.

The research calls for a global dialogue based on a multi-stakeholder approach and a holistic solution which goes beyond protective responses like blocking and filtering of content, and focus on empowering young people both online and offline.

In the next six months, the research will be finalized and published.

Sofia Rasgado, from the Council of Europe, shared the good practice of a Portuguese campaign to decrease hate speech, cyber bullying and cyber hate, based on human rights education, youth participation and media literacy. Google’s William Hudson argued that content take-down and censorship are insufficient to combat radicalization, and he presented Google's ongoing counter-speech efforts to build a platform for true solidarity and understanding.

Barbora Bukovska, from Article 19, expressed her concern that the lack of definition of the concept of radicalization could lead to violations of human rights. She welcomed UNESCO’s promotion of positive policy measures, including various counter-speech methods, arguing that these are a more effective tool to fight the underlying social causes leading to radicalization.

From Ranking Digital Rights, Rebecca MacKinnon alerted that civil society is often under dual attack by governments and extremist groups, and pleaded that the protection of human rights online and offline and the defense of civil society and independent journalists are crucial to solve the problem of radicalization in the long run.

Participants raised a number of questions related to criminalization of hate speech, freedom of religious expression, balancing rights, personalized content, etc.

A common theme was that all stakeholders need to critically assess the problem of youth radicalization and join their efforts to invest in holistic and effective solutions that take consideration of human rights implications and gender issues, and which take counter-measures and youth empowerment actions.

Source: UNESCO

Study: How Digital Media May Change the Way You Think

New study shows that using digital platforms such as tablets and laptops for reading may make you more inclined to focus on concrete details rather than interpreting information more abstractly,In a new study, researchers reveal that reading comprehension and problem solving success were affected by the type of reading platform, either digital or non-digital, used.

The study, published in the in the proceedings of ACM CHI '16, the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, was done in hopes to better understand if processing the same information on one platform or the other would trigger a different baseline "interpretive lens" or mindset that would influence construal of information.

"There has been a great deal of research on how digital platforms might be affecting attention, distractibility and mindfulness, and these studies build on this work, by focusing on a relatively understudied construct," said lead author Geoff Kaufman, an assistant professor at the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, in a statement.

In order to determine if there is a relationship between reading platforms and construal cognition, researchers conducted four studies. More than 300 volunteers with age ranging from 20 to 24 years old participated in the studies. Each study was then joined by 60 to 100 participants.

In conducting their studies, researchers are careful in making most of the variable to be as constant as possible. For example, the same print size and format was used in both the digital and non-digital platforms.

In one of the studies, participants were asked to read a short story by author David Sedaris on either a physical printout (non-digital) or in a PDF on a PC laptop (digital), and were then asked to take a pop-quiz, paper-and-pencil comprehension test.

After analyzing the results of the test, researchers found out that participants using the non-digital platform scored higher on inference questions with 66 percent correct answers on the abstract questions, compared to 48 percent of correct answer of those using the digital platform.

On the other hand, participants using the digital platform scored better on concrete questions with 73 percent correct, as compared to those using the non-digital platform, who had 58 percent correct.

When the participants were asked to read a table of information about four, fictitious Japanese car models on either a PC laptop screen or paper print-out, and were then asked to select which car model is superior, 66 percent of the participants using the non-digital platform have reported the correct answer, while only 43 percent of those using the digital platform got the correct answer.

Source:www.natureworldnews.com

7 Good reasons for Digital Youth Participation

Are you not yet convinced that digital youth participation can be fruitful? In this article we show why utilizing digital tools is particularly effective and key to successful youth participation processes.Good youth participation facilitates dialogue between different generations, encourages innovative ideas, strengthens democratic competences but also leads to more suitable policies and planning. Hence, the level of (digital) youth participation can be a location factor for municipalities.

Youngsters need opportunities to participate in politics, which go beyond the classical types of engagement. They need participation processes that are appropriate for their age group, their environment and lifestyle. Digital (media) tools offer various innovative ways to connect, discuss issues and take part in decision-making.

Why You Should Opt for Digital Youth Participation

1. More participation - irrespective of time and place

Developing opinions, discussing them with others and finally voting on them takes time. Many youngsters do not have the possibility or motivation to take part in formal offline participation after their busy day at school, university or work. Digital tools, however, can mitigate this issue by offering to take part whenever and from wherever young people would like to engage – online.2. Greater transparency - open processes

Digital tools can comprehensively document the entire participation process: from general information and idea collection to voting and final implementation of the results. Hence, they offer an overview of the process – also for those people, who are not actively taking part. At the same time this transparency promotes understanding and trust in the political and administrative processes.3. Better overview - comprehensible decisions

Good dialogues offer everyone the possibility to share their views on the issue at hand, this way creating a vast number of inputs, which need to be structured and evaluated. Many online tools provide search and filter options. Also the course of discussion can be documented and reviewed easily with the help of these tools. Hence, participants are enabled to keep an overview of the discussion’s development, which easier renders the preparation for decisions.4. Youth-friendly - targeting the young audience

Almost all young people use digital media on a daily basis. They share photos, videos, information and opinions but also discuss issues. In light of this, it is simply logical to offer digital participation tools to utilize the digital spaces where youngsters are already engaging every day. This increases the acceptance of the process. Furthermore, using digital tools facilitates dialogue between political decision-makers, administrations and young people.5. More political involvement - reducing barriers

With digital tools, youngsters can easily from anywhere become active in shaping their own environment. Particularly, those young people who are usually politically inactive are likely to be reached with low-threshold digital participation projects. These show them that political decision-making can be fun and that it is actually possible to change something. When experiencing this possibility to achieve something, they are more likely to also start to participate in other, more classical, ways of engagement.6. A location factor - keeping pace with the times

Young people want to participate. Yet, decision-makers need to provide them with attractive, modern, digital opportunities and ways to do so. Thereby, decision-makers will benefit as they are creating a new location factor: they become digitalized and participation-friendly. Youngsters’ motivation will increase when they see that their engagement leads to results.7. More participation – increasing the network

Digital participation processes can easily be connected with social media in order to increase their reach. Participants can share their arguments with others and motivate them to join and take part. In just a few clicks, friends and acquaintances will be able to participate themselves. Therefore, more youngsters can be addressed with digital participation tools.Many thanks to jugend.beteiligen.jetzt for the permission to publish their German article in a translated version.

Source: www.euthproject.eu

Digital Media and the Art of Engagement

In the last couple years, new digital media publications have been popping onto the scene with intensity. We’ve seen print magazines and dailies frequently revamp, re-brand and work continuously to be more interactive, engaging and immediate.Today we all participate in online experiences and interact with content that is up-to-the-minute, interactive, beautiful and personally relevant. There have been major shifts in reader expectations, journalistic tools and publishing business models.

These changes, aided by technology, have been driven by changes in reader behavior: we grab the iPad or smartphone when we wake up to browse the morning’s headlines, listen to podcasts of news shows and catch the replay of that clip everyone is talking about. And while there were obvious growing pains across the media landscape in the early stages of digital technology, the industry is clearly rebounding.

Success for these companies, however, is not judged by page views, number of comments or shares. These are some of the most respected names in the business — some hundred year-old companies and other young upstarts — that use technology to strengthen and fortify the relationship with readers and build trust in the brand. The media landscape has upped its game. So, what is working across this digital media landscape?

Most of us have read Harry Potter, and have imagined what the magical newspaper, The Daily Prophet, might be like with its waving people and moving pictures. Today with digital, we can experience articles, watch video clips — hear the sounds and see the highlights. Heck, we have options to listen to individually curated playlists to accompany our morning scans of the headlines. Yet, the brands that can match that incredible digital content with an equally appealing human element — they will be the ones who thrive.

Today’s news content is phenomenal in its own right and when it is paired with a card-stock mailed invitation to attend a members-only event with a publication’s award-winning photojournalist, an opportunity for a long-lasting reader relationship is opened.

Digital media winners won’t just provide news, they will develop relationships with readers and continually offer them unique opportunities to engage and feel a part of something bigger. As an example, once a new reader signs up, News UK — a British newspaper publisher and subsidiary of News Corp. — sends every new member a customized personal invitation to meet with the editor. Additionally, all members receive honest-to-goodness chocolates around Christmas and Easter. Think of the surprise and delight to once again feel such a personal connection with a daily paper.

There is also good plain fun to be had- people love to laugh. News UK’s paper The Sun used the power of social media to create a hilarious seasonal campaign. Called the “Hangover Hit Squad,” the staff literally delivered survival kits to those who complained of holiday hangovers on social media sites.

It is about relationships, but let’s not kid ourselves, it is also about economics. A bonded relationship between reader and publisher opens the doors for journalists to receive higher pay, for ad revenue to become a smaller part of the equation, and for digital subscriptions to enjoy same worth and price, if not more so, than their print counterparts.

Now content costs more than technology. Google, Facebook and other tech companies will always be ahead of the news company because they don’t have to pay for content. What is exciting in digital media is the emerging ability to create an entirely new ad model to not just economically support, but to enhance the overall experience. Ad models just got a lot more exciting with the introduction of the tablet. We’re seeing readers spend, on average, ten minutes longer reading the news on their tablet than they do with a print publication.

The model that is developing — how can we get the technology enhanced and make that truly interactive, yet non-intrusive, ad? Think of a newspaper, the best glossy experience — the ads are just as much a part of that as the articles. Cutting-edge, engaging digital advertising that flies off the page and delights the reader in a way black and white print ads just can’t — that’s the future. If we can crack that, the journalists are safe.

Good publications realize that journalism is a profession that should pay quite well, which makes news content expensive to deliver. With a free model, publications run the risk of creating a barren job market for good journalists. With the dissipation of quality journalism, the quality of content will go down, and along with it, the trust-powered relationship with your readers.

At the end of the day, people are willing to pay for great journalism — even more so if they are feel they are an intimately important part of the community. When readers are offered opportunities to develop relationships with editors, writers, photojournalists and staff or curate playlists according to what they are reading- they are significantly more engaged. So, while digital media is relatively new, the art of engaging people and creating community is a timeless art. The economics follow.

Co-authored by Tien Tzuo, founder and CEO of Zuora; and Katie Vannek-Smith, CMO of News UK.

Source: www.wired.com

Eat, sleep, protest, repeat - 5 ways teenagers can realise their inner activist

As I sat in a fancy hotel surrounded by adults, the question arose as to how big of an invitation has been given to teenagers to become involved in being creators of change. There were two other teenage girls in the room, also on work experience, in many ways we had invited ourselves to that discussion on how change happens. In a similar way, we must invite ourselves to be those creators of change – That’s the thing about us teenagers, we have a way of sneaking in places you’d never expect! Activism is defined as “Using vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change”. Change is often a journey as, in my opinion, is activism.So, from my modest perspective, here are five ways to begin that journey.

1. Educate yourself:

Learn as much as you can about the issues you care about. Read books, search websites and talk to other people. Think of yourself as a detective trying to find every piece of information you can, it will help you form your own opinions and make you more aware of other issues. Also, try to learn about what’s happening in the world at present, the news is a vital tool in your activist kit.2. Get involved:

Even if you feel like you don’t know enough or that you’re inexperienced, everyone has to start somewhere. Join a youth group working on certain issues or even better, start one! Volunteer with a charity working on local or global issues. Even sign an online petition, or follow a Twitter page, social media is your best friend as a modern activist. Find out how you can get involved, once you make that step you won’t be able to look back.3. Be Driven:

Find out about causes you’re passionate about and support them as much as you possibly can. If you don’t think there’s any sort of group or activists out there that are doing what you’re interested in make your own. How and why you become involved to make change is completely up to you. When you have begun to get involved, make sure to remind yourself why and stay motivated!4. Talk to other activists:

Whether this means following a lifelong activist on Twitter, or simply talking to a local youth worker who is interested in the same issues as yourself, talk to other young people, tell them what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, get them involved. Finding out the ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ of others creating change is a vital part of learning for any activist.5. Repeat:

As I’ve already said staying motivated is imperative in making any kind of change, but if you’re passionate about what you’re doing, this shouldn’t prove too difficult. Try find some time to stay on top of different projects that may be happening. It can be hard to balance but it’s so worth it when you realise you have the ability to make a difference.I had never really considered myself to be an activist, sure I’m involved with youth politics, youth groups working for social change and the odd community project. But, an activist? I didn’t think so. What I learnt on my week of work experience with 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World is that in fact most of us are already activists, we just need a bit of a push sometimes. Do you only buy fair trade bananas? Consider yourself an activist. Have you ever signed an online petition that affected change? You’re most likely an activist. Ever done a project on human rights? Activism at its finest. In today’s fast paced world activism comes in all shapes and sizes, most of the time you don’t even realise it’s happening. Thanks to social media and our generation, everyday activism is a beautiful thing and I really hope it continues to shape and create change for many generations to come.

I will finish with one of my favourite quotes that a fellow activist shared with me.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world indeed it’s the only thing that ever has” – Margaret Mead

This blog is a reflection from Tara Hoskins having spent a week with 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World as part of her TY work experience in February 2017.

Source: developmenteducation.ie

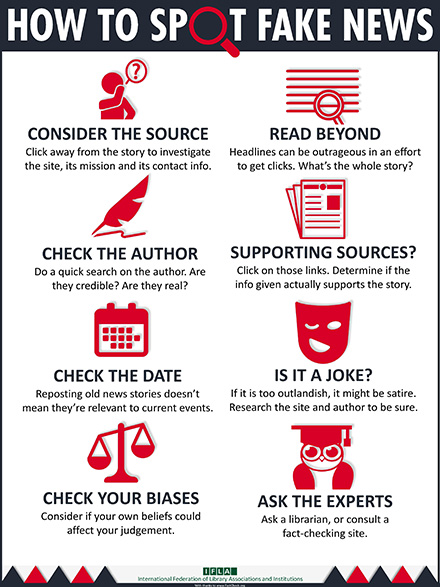

How To Spot Fake News

Critical thinking is a key skill in media and information literacy, and the mission of libraries is to educate and advocate its importance.Discussions about fake news has led to a new focus on media literacy more broadly, and the role of libraries and other education institutions in providing this.

When Oxford Dictionaries announce post-truth is Word of the Year 2016, we as librarians realise action is needed to educate and advocate for critical thinking – a crucial skill when navigating the information society.

IFLA has made this infographic with eight simple steps (based on FactCheck.org’s 2016 article How to Spot Fake News) to discover the verifiability of a given news-piece in front of you. Download, print, translate, and share – at home, at your library, in your local community, and on social media networks. The more we crowdsource our wisdom, the wiser the world becomes.

Download the infographic

Translations

- Español (Spanish) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Français (French) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Deutsch (German) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Русский (Russian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- 中文 (Chinese) [coming soon]

- العربية (Arabic) [PDF] | [JPG]

- বাংলা (Bengali) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Български (Bulgarian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Hrvatski (Croatian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Čeština (Czech) [coming soon]

- Dansk (Danish) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Nederlands (Dutch) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Eesti (Estonian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Suomi (Finnish) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Ελληνικά (Greek) [PDF] | [JPG]

- עִברִית (Hebrew) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Magyar (Hungarian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Íslenska (Icelandic) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Italiano (Italian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- 한국어 (Korean) [PDF] | [JPG]

- 日本語 (Japanese) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Latviešu (Latvian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Lietuvių kalba (Lithuanian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Norsk bokmål (Norwegian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Norsk nynorsk (Norwegian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Polski (Polish) [coming soon]

- Português (Portuguese) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Românește (Romanian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Cрпски (Serbian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- af Soomaali (Somali) [coming soon]

- Svenska (Swedish) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Türkçe (Turkish) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Українська (Ukrainian) [PDF] | [JPG]

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese) [coming soon]

- Cymraeg (Welsh) [PDF] | [JPG]

Social media activism in repressive environments

Activists in the global south talk about integrating social media and offline networks to campaign with limited internet access under repressive regimes.Egyptians who ousted Hosni Mubarak in 2011 did not decide to occupy Tahrir Square after spending a day chatting on Facebook and Twitter. They spent years building alliances and an infrastructure that could stand up to the regime’s censorship and repression. Social media supported alliances and infrastructure–becoming the right tool at the right time.

Six years later, social media connects activists, organisers and NGOs seeking change around the world. In many countries, however, social media access remains a privilege. Smartphones, laptops and internet access can be very expensive. “You can buy a motorcycle or an acre of land for the cost of an iPhone 7,” said Philip Kabuye, IT support and research officer at Action Aid Uganda.

Repressive regimes are also pushing social network activism offline. People connect in everything from small businesses, houses of worship and informal gatherings of jobless youth.

Physical spaces are critical to campaigner networks. They’re often the only alternative for those living under repressive regimes. And as digital surveillance becomes normalised, organisers in the West find face-to-face networks an essential complement to their online communications. Integrated use of physical objects (think T-shirts, billboards and “pussy hats“) and social media symbols like hashtags become ways to extend the reach of digital campaigns in difficult environments.

We spoke with activists and organisers from several parts of the global south to understand how they see social media and offline networks working together in locations with repressive regimes and/or limited access to social platforms.

Circumventing censorship

Traditional media outlets operating under repressive regimes find it difficult to give their audience the whole story–if that is even their goal. Radio, television and print news outlets are sometimes state-owned. Larger independent media houses may experience intimidation. Their response is often self-censorship.

Governments find it much more difficult to influence social media–though it happens.

“The strength of social media is that you reach a large amount of people fast, often with primary information,” said Rachael Mwikali, a Nairobi-based feminist activist.

The fake news epidemic demonstrates that destabilising the truth can be an effective government (and campaigner) response. Hence, censorship is just one problem campaigners face when using social media. And shifting perceptions in social media (and offline) is a powerful tactic.

The power of the perceived reality

Famed community organizer Saul Alinsky wrote in Rules for Radicals, “The threat is more terrifying than the thing itself.”

On August 19, 2015, Ugandan activist Norman Tumuhimbise and fellow youth activists of the Jobless Brotherhood freed pigs around Kampala, the capital city. Attached to them was a note warning the government to put an end to its corruption, lest the activists take action to make the country ungovernable.

That night, Tumuhimbise disappeared. Friends worked tirelessly to advocate for his release. Their pleas fell on mostly deaf ears of embassies, human rights groups and journalists who feared the repercussions of covering such a story.

The Interparty Youth Platform, a coalition of youth from seven political parties, took matters into their own hands. While others were busy organizing a vigil to declare Tumuhimbise kidnapped and killed by the state, they published a simple graphic on Facebook: a red X over the victim’s face under the phrase “Dead at hands of a dictator.”

Late that night, Tumuhimbise was pushed out of a car near his home where he had been abducted. He suffered a week of torture and dehydration in a cold underground cell. The claim he had been killed was enough to push the state to prove otherwise.

“I think the posting of that graphic online helped save my life,” Tumuhimbise later explained.

Social media as trickle-down campaigning

“Using social media is expensive,” said Mwikali. “We use it for advocacy, WhatsApp group discussions and fundraising, but it is not accessible to people at the grassroots.”

Perhaps this is why, during the recent political transition in the Gambia, most digital campaigning to support incoming president Adama Barrow seemed to be concentrated in the capital of Banjul.

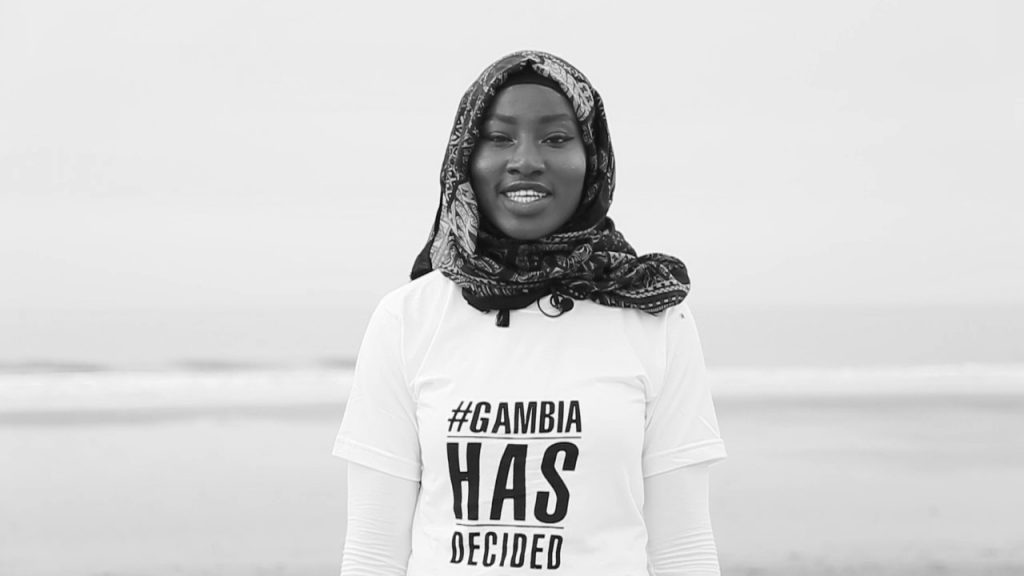

When 22-year dictator Yahya Jammeh was defeated at the polls December 1, he initially conceded to the victor. Jammeh reneged a week later, claiming the vote was rigged. This prompted young Gambians to share information on Jammeh’s coup attempt and their resistance against it using #GambiaHasDecided.

The hashtag assisted online coordination and flow of information in the heavily censored Gambian media. Youth took the hashtag offline, wearing it on their T-shirts.

Numerous young people sporting the #GambiaHasDecided T-shirt were arrested, but eventually released. The resolve of those wishing for an end to Jammeh’s rule seemed to strengthen every day. The hashtag itself is still trending.

“Recently, lots of Gambian youths ventured through a deadly trip to get to Europe,” noted one Gambian activist who preferred anonymity. “They are now supporting their families. This has made many people express themselves without fear of losing their jobs. Social media has played a big role in this political event.”

“Recently, lots of Gambian youths ventured through a deadly trip to get to Europe,” noted one Gambian activist who preferred anonymity. “They are now supporting their families. This has made many people express themselves without fear of losing their jobs. Social media has played a big role in this political event.”

Diaspora Gambians are using networks like Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp to collect contributions for cloth to be worn at Barrow’s swearing in. They are also distributing phone numbers to call should anyone want to receive a few yards of the cloth and attend the inauguration. The purpose of online activity is to organize offline participation.

Access to modern technology–and its use, including social media–is often concentrated in urban areas. Rural areas of Kenya, Uganda, and the Gambia have more direct ways of organizing, such as face-to-face meetings. There is little evidence that social media mobilisation will trickle down to rural Africans on a large scale, but it is certainly a starting point for young urbanites.

Using social media AND acknowledging its limited reach in marginalised communities is a good rule of thumb. Campaigners across Africa are using social media but few rely on it. The strongest efforts supplement upcountry outreach strategies with on-the-ground actions and outreach to carry messages, including face to face communications and physical objects (T-shirts are just one example).

Source: www.mobilisationlab.org

Why Youth Marketing isn't that Complex

Unfortunately, marketing to the youth demographic of our society is seen by some in our industry as an otherworldly skill that only a special few have mastered. With 90% of briefs that agencies receive targeted at this market, we need to have a much better understanding of this audience.We are all guilty of being a bit too focused on the end goal, our KPI’s, meaning we are constantly looking for that magical ingredient - be that a social media platform, an influencer or a media partnership that will make all the young people instantly share your content online making it go viral, and making you look cool in front of your peers and clients because you 'get' the 'yoof' of today.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but there isn’t an ingredient or hack or a preferred social media platform that you need to be on to make them interested in your product. What they want is for you to be is real.

How can you as a brand do this? Well here are my five key takeaways from Youth Marketing Strategy 2017 talks that will help you become a real brand and have a more meaningful relationship with your audience.

1. Master the art of conversation: Become a storyteller

Put simply, young people want brands to talk to them more. Don’t just attend a fresher’s fair or send them a voucher and then just forget about them, keep them engaged and keep talking to them.

This doesn’t mean you should start churning out content for the sake of it across every single channel. You need to ensure that your message and tone are right, and land at the right time, on the right channel for the right people.

A recent survey from Bam UK found that 24% of students weren't familiar with at least two of the major high street brands, but over half would go on to engage with them later. The first three months are key, as this is where their loyalty builds and sticks.

2. Don’t be a fraud – authenticity is key

Once you’re talking more to your audience, you need to ensure what you are saying is adding value to the conversation and to their lives.Just as you would in real life, stop and think before you speak. Does your brand have the authority to speak about this topic? If yes then do it; if not, well don’t – it’s that simple.

3. Provide the experience

Part of becoming an authentic, real brand means connecting with your audience in the real world. This is a great way to get your brand message out, but also provide people with a really unique experience that they can connect with.

This doesn’t mean simply visiting a festival and that’s it. Ensuring there is a socially shareable element to the experience is vital. This generation has a FOMO (fear of missing out) and they want their network to see all the unique experiences they have had. So ensuring this has social currency is key to extending your reach organically.

4. Don’t jump ship

“According to the latest data in an industry report x number of 16 to 24-year-olds use x social media platform.” Cue all agencies and brands running onto said platform to engage with their audience.

There are so many channels out there and targeting an audience that is digitally native means you need to carefully consider what you’re doing. Any content (ads included) need to feel native to the platform, with the correct messaging. Don’t create a new social account because all the cool kids are there. Think about whether it’s a relevant platform for your brand and your message, and will this be an always-on strategy or only viable for a one-off campaign.

5. Relax

Brands need to relax the control over their content. Giving it the space to grow and evolve online by co-creation is vital to help ensure it lives longer, is relevant and resonates with the right audience.

Cancer Research understood this with its Stand Up to Cancer campaign and discovered that content created by a third party (creator/influencer) that they ‘hero-ed’ outperformed their own content. This was because the content created had an added layer of authenticity to it.

Although we keep talking about young people as some kind of an alien market, they aren’t. Yes, they are more digitally savvy than other demographics and more on trend. They are, however, still people who want and actively seek genuine and meaningful connections. Our responsibility is to ensure we do this not just for them but for all our consumers.

Source: digitalmarketingmagazine.co.uk

Youth, Activism and the Power of Digital Media

As more and more young people find themselves drawn to the world’s issues, the question of how to go about addressing them becomes increasingly important. One area that has proved to be particularly contentious is that of digital media. While there are plenty of arguments for the use of social and online platforms, there have also been various attacks on the efficiency of online activism.In particular, many have debated the subject of “slacktivism” – the idea that most online activism is ineffective because of the limited commitment it takes to share media, sign a petition or post material. This article will highlight why this is an important issue for young people, how online media can be used for activism and the pros and cons of doing so.

How young people use the internet as an activism tool?

Young people are in a prime position to use technology and the internet as a tool – many of us have grown up with various forms of technology in the home and at school, we understand how to use social media to our advantage and the internet isn’t new or intimidating to us.

This isn’t to say that the older generation aren’t able to do the same things or even better - but for most young people, using several kinds of digital media on a daily basis has just become another aspect of our lives. Even the most skilled adult users have still had to adjust from a time before this became the norm.

When it comes to activism, we can quickly reach more people than ever before in a variety of different ways. From lower levels of action such as signing petitions or sharing an article to more time-consuming efforts like posting a blog or video, activists have an array of tools at their disposal. Spreading awareness and organising gatherings or events no longer has to take up a lot of time and resources, meaning these can be directed elsewhere. [CT1]

Educational resources in the form of articles and videos are plentiful and often thorough (a good example is that of Laci Green, a feminist YouTuber who frequently creates videos covering gender issues, sex positivity and self-care). These platforms are useful for all activists in both self-education and posting our own media to help others.

'Slacktivism'?: the pros and cons of online activism

However, like all systems, there are of course limitations to online activism and some of its best qualities are also its worst. As anyone can post anything, not everything is properly researched, which can lead to a potential spread of misinformation, and even those that are produced carefully can suffer from hateful trolls among more positive commenters. (See our video below for a few ways to stay smart online).

Since the ALS Ice Bucket challenge and Kony 2012, there has been a lot of debate about whether online activism is even worth pursuing at all. Many lower level forms are dismissed as “clicktivism” or “slacktivism”, insinuating that there’s no real effect and that the use of online media is a fad that merely makes people feel good about themselves.

While this could apply to less effective actions such as changing your profile picture to show support or liking a post about an issue, I still think it’s somewhat misguided. I’m not sure people who do just these things consider themselves activists or get any great sense of philanthropy – we like things because we like them, not because the act of clicking a little blue hand is going to change the world.

Other higher level forms of activism, such as signing petitions, sharing media and asking others to donate to a cause (especially when you’ve already donated yourself) don’t deserve this ruthless dismissal. While they take just seconds to carry out, their full effect can be staggering. Petitions have existed for centuries, but websites like change.org have made the process far more straightforward and much quicker. Even if the petition itself doesn’t achieve the desired change, it will have taken less time and effort than a petition that took weeks to collect by hand that received the same result.

Sharing media can raise awareness, educate and motivate great numbers of people in ways that can’t be measured – there’s no knowing how many people might be deeply affected or who might be spurred into a lifetime of action from one person making a particular issue known to them.

Donations are also easier and safer online for both charitable worker and donor – people may be reluctant to give money on the high-street and collectors have to stand and be rejected for hours, but online the process is secure, quick and easily shared with others. And clearly, economic support makes a very substantial difference to those ultimately benefiting from it.

Opening up new channels for change

Those criticising online media often tell users to step away from the computer and go out to volunteer or donate, ignoring the fact that not everyone has lots of money to donate or time to spare, even if they care about the cause deeply. In addition to the points mentioned above regarding donation, online media can allow people to donate as little or as much as they feel able. Digital activism allows those with little time or spare cash a chance to participate in a cause they care about, without putting undue pressure on themselves. Causes are important, but self-care is too – activists can’t help anyone if they’re overly stressed or fatigued from trying to do too much.

Saying “step away” also indirectly dismisses those who are actually donating and volunteering offline, but are using additional platforms to reach a wider audience in more efficient ways. Online activism often goes hand in hand with physical activism, as real passion for a cause leads us to find as many ways to help as we can. It also allows people who want to support multiple causes the chance to help each on different levels (for example, I care about gender-based violence, LGBT+ issues and animal rights, but much of my time goes into the first one – online activism allows me to support the other two as well).

Not everyone can - or should - be an activist

Finally, not everyone has to be an activist. Obviously, improving the world would be a lot faster and easier if every single person wanted to spend their lives working on an issue. But not everyone does and that’s completely fine (probably better than fine, there would be chaos if everyone upped and left their day jobs!). Activism should be pursued out of passion and determination, not guilt.

Youth in particular are already facing unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression from mounting pressure in social and educational spheres. Adding more onto that by saying “Oh, and you have to save the world too” can only end badly. Digital activism, on any level, has allowed us to shed the mentality that we’re just individuals who can’t have any real effect because the world and these issues are just too big.

Activism at its core has always been about bringing people together, knowing that a thousand voices together can achieve great things. Even if a person doesn’t want to spend their days actively fighting for a cause, they do a lot more by clicking “share” than doing nothing at all.

While there are a few downsides to the internet in general, the use of digital media can be immensely rewarding. No one is saying that online activism should replace physical activism and as long as we’re careful, the internet can be an endlessly useful tool to support the first-hand work that is already happening.

To dismiss online activism entirely is to dismiss one of the most vital and ever-improving instruments for change that we have in the modern day.

Source: youthforchange.org

How a new wave of digital activists is changing society

Digital activism has transformed political protest in the last two decades. Smartphones and the internet have changed the way political events, protests and movements are organised, helping to mobilise thousands of new supporters to a diverse range of causes. With such activity becoming an everyday occurrence, new forms of digital activism are now emerging. These often bypass the existing world of politics, social movements and campaigning. Instead, they take advantage of new technologies to provide an alternative way of organising society and the economy.We've become used to the idea of digital activism and social media being used to publicise and grow political movements, such as the Arab Spring uprisings in the Middle East and the anti-austerity movement Occupy. Activists, such as those in recent French labour protests, can now live stream videos of their actions using apps such as Periscope while online users contribute to the debate. In Barcelona, the party of new mayor Ada Colau drew up its electoral programme with the help of over 5,000 people, in public assemblies and online, including the formation of network of cyberactivists, SomComuns.

So-called hacktivist organisations such as Anonymous regularly attack the computer networks of the rich and powerful, and even terrorist organisations such as Islamic State . The recent Panama Papers follow similar revelations by Wikileaks and Edward Snowdenas examples of "leaktivism". Here, the internet is used to obtain, leak and spread confidential documents with political ramifications. The Panama leaks have led to protests forcing Iceland's prime minister to step aside and calls for similar action in the UK.

Quiet activism

All these forms of online activism are essentially designed to force change by putting political pressure on leaders and other powerful groups in the real world. But new kinds of digital activity are also attempting to change society more directly by giving individuals the ability to work and collaborate without government or corporate-run infrastructures.

First, there are quieter forms of digital activism that, rather than protesting against specific problems, provide alternative ways to access digital networks in order to avoid censorship and internet shutdowns in authoritarian regimes. This includes bringing internet access to minority and marginalised groups and poverty-stricken rural areas, such as a recent project in Sarantaporo in northern Greece.

But it also involves more unusual technological solutions. Qual.net links your phone or computer to an ad-hoc network of devices, allowing people to share information without central servers or conventional internet access. In Angola, activists have started hiding pirated movies and music in Wikipedia articles and linking to them on closed Facebook groups to create a secret, free file-sharing network.

Second, there are digital platforms set up as citizen, consumer or worker-run cooperatives to compete with giant technology companies. For example, Goteo is a a non-profit organisation designed to raise money for community projects. Like other crowdfunding platforms, it generates funding by encouraging lots of people to make small investments. But the rights to the projects have been made available to the community through open-source and Creative Commons licensing.

The example of the Transactive Grid in Brooklyn, New York, shows how blockchain – the technology that underpins online currencies such as Bitcoin – can be used to benefit a community. The Transactive blockchain system allows residents to sell renewable energy to each other using secure transactions without the involvement of a central energy firm, just as Bitcoin doesn't need a central bank.

These platforms also include organisations that help people to share goods, services and ideas, often so that they can design and make things in peer-to-peer networks – known as commons-based peer production. For example, fablabs are workshops that provide the knowledge and hardware to help members make products using digital manufacturing equipment.

Greater democracy and co-operation

What links these new forms of digital activism is an effort to make digital platforms more democratic, so that they are run and owned by the people that use and work for them to improve their social security and welfare. Similarly, the goods and services these platforms produce are shared for the benefit of the communities that use them. Because the platforms are built using open-source software that is freely available to anyone, they can be further shared and rebuilt to adapt to different purposes.

In this way, they may potentially provide an alternative form of production that tries to address some of the failures and inequalities of capitalism. Using open tools, currencies and contracts gives digital activists a way to push back beyond the louder activity of aggressive cyberattacks and opportunistic social media campaigns that often don't lead to real reform.

The internet has always allowed people to form new communities and share resources. But more and more groups are now turning to a different set of ideological and practical tools, creating cooperative platforms to bring about social change.

Source: phys.org

5 Online Tools For Activists, By Activists

Susannah Vila directs content and outreach at Movements.org, an organization dedicated to identifying, connecting and supporting activists using technology to organize for social change. Connect with her on Twitter @szvila.

Why are social networks powerful tools for causes and campaigns? Many times, people begin to engage in activism only after they’ve been attracted by the fun stuff in a campaign — connecting with old friends and sharing photos, for example. When they witness others participating, they’ll be more likely to join the cause. With socializing as the primary draw, it’s become easier for organizers to attract more and more unlikely activists through social media.

But once a campaign reaches its critical mass, activists might think about moving to other platforms made with their needs — especially digital security — in mind. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter will remain standard fare for online activism. But the time is right for niche-oriented startups to create tools that can supplement these platforms. Here are a few worth investigating.

1. CrowdVoice

Similar to the social media aggregating service Storify, but with an activist bent, CrowdVoice spotlights all content on the web related to campaigns and protests. What’s different about it? Founder Esra’a al Shafei says “CrowdVoice is open and anyone is a contributor. For that reason, it ends up having much more diverse information from many more sources.” If one online activist comes across a spare or one-sided post, he can easily supplement information. Furthermore, campaign participants can add anecdotes and first-hand experiences so that others can check in from afar. CrowdVoice makes it easier for far-flung audiences to stay abreast of protests and demonstrations, but it also helps organizers coordinate and stay abreast of other activist movements.

If one online activist comes across a spare or one-sided post, he can easily supplement information. Furthermore, campaign participants can add anecdotes and first-hand experiences so that others can check in from afar.

CrowdVoice makes it easier for far-flung audiences to stay abreast of protests and demonstrations, but it also helps organizers coordinate and stay abreast of other activist movements.

2. Sukey

During London’s UK Uncut protests this year, police used a tactic called “kettling,” or detaining demonstrators inside heavy police barricades for hours on end. In response, UK Uncut activists created a mobile app to help one another avoid getting caught behind the barricades. The tool, Sukey -- whose motto is “keeping demonstrators safe, mobile and informed” — helps people steer clear of injuries, trouble spots and violence. Sukey’s combination of Google Maps and Swiftriver (the real-time data verifying service from the makers of Ushahidi) also provides a way for armchair protesters to follow the action from afar. Users can use Sukey on a browser-based tool called “Roar,” or through SMS service “Growl.”

3. Off-the-Record Messaging

“Off-the-Record” (OTR) software can be added to free open-source instant messaging platforms like Pidgin or Adium. On these platforms, you’re able to organize and manage different instant messaging accounts on one interface. When you then install OTR, your chats are encrypted and authenticated, so you can rest assured you’re talking to a friend.

4. Crabgrass

Crabgrass is a free software made by the Riseup tech collective that provides secure tools for social organizing and group collaboration. It includes wikis, task files, file repositories and decision-making tools.

On its website, Crabgrass describes the software’s ability to create networks or coalitions with other independent groups, to generate customized pages similar to the Facebook events tool, and to manage and schedule meetings, assets, task lists and working documents. The United Nations Development Programme and members from the Camp for Climate Action are Crabgrass users.

5. Pidder

Pidder is a private social network that allows you to remain anonymous, share only encrypted information and keep close track of your online identity -- whether that identity is a pseudonym or not.

While it’s not realistic to expect anyone to use it as his primary social network, Pidder is a helpful tool to manage your information online. The Firefox add-on organizes and encrypts your sensitive data, which you can then choose to share with other online services. It also logs information you’ve shared with external parties back into to your encrypted Pidder account.

Source: mashable.com

Digital and Online Activism

Increasing accessibility and the ability to communicate with thousands of citizens quickly has made the internet a tool of choice for individuals or organisations looking to spread a social message far and wide. Independent activists the world over are using the internet and digital tools to build their community, connect with other similar-minded people outside their physical surroundings as well as lobby, raise funds and organise events.

Simply put, digital activism is where digital tools (the internet, mobile phones, social media etc) are used towards bringing about social and/or political change. Examples of digital activism are scattered throughout the '80s however, things started to really snowball with the advent of web 2.0 and the dot com boom. The introduction and rapid growth of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter from 2004 onwards helped buttress digital activism to the point where entire campaigns can now be run online (sometimes with little to no offline component) and still have a wide reach. But is reach enough? Many argue that digital tools alone do not suffice when it comes to galvanising people towards creating change. According to online activism think tank Meta-Activism Project, digital activism should serve six key functions: shaping public opinion; planning an action; sharing a call to action; taking action digitally; transfer of resources.

A good timeline of digital activism around the world can be found here.

The Tools

The tools used by digital activists are vast and the list changes constantly in line with the rapid general evolution of technology.

- Online petitions. Websites such as Change.org and MoveOn.org are hubs of online activism, where people can communicate with others worldwide regarding their cause. MoveOn.org initially grew from a small petition that two Silicon Valley entrepreneurs sent to some family and friends in the late ‘90s, asking for their support in telling the White House to “move on” from the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky scandal to more pressing issues facing the country.

- Social networks. Sites with high usage numbers such as Facebook and YouTube have proven beneficial in spreading a message, garnering support, shining information on a subject that might otherwise be overlooked by mainstream media. Protests in 2011 in Tunisia and Egypt against their respective governments were in part organised and promoted via Facebook.

- Blogs. Essentially a form of citizen journalism for the masses, blogs provide an effective means of non-filtered communication with an audience about any topic and have been used in numerous online campaigns.

- Micro-blogging. Micro-blogging sites such as Twitter are used to help spread awareness of an issue or activist event. Twitter's hashtag function, which allows people to have their tweets contribute to a multi-user conversation by typing a keyword or phrase preceded by a hashtag, is used frequently as a digital tool for spreading a message. The Chinese equivalent to Twitter, Weibo is subject to scrupulous government censorship however people circumvent this blockade by using code words when writing about issues that might be government-sensitive.

- Mobile phones. Controversy surrounding the 2007 presidential elections in Kenya led to the introduction of Ushahidi Inc., a company which developed a piece of software that allowed people to send texts and pictures of violence following the elections which were plotted geographically on a Google map. The software has since been used to plot activity in disaster zones following earthquakes in Haiti and New Zealand and flooding in Australia and the USA.

- Proxy servers. As a means of circumventing government intervention when it comes to online protesting, many people employ proxy servers, which act as intermediaries between a user and a site, thus essentially circumventing national restrictions on any site. In 2009, student protesters in Iran took to social media to voice their concern over the contentious reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. This led to a cat and mouse game of the government trying to identify which media were being used by the protesters to communicate (social networks and then eventually proxy servers) and shutting them down.

Getting the Message out There

One of the biggest benefits of using digital tools for positive change is the ability to connect with a large community and, if applicable, globalise a campaign's goals. The interconnected nature of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter lend themselves easily to information sharing, meaning an activist can post a slogan, picture or details about an issue, share it with friends, plug into likeminded online communities and distribute info through their networks in a much less time and energy-consuming way than more traditional methods of going door-to-door or standing on street corners and asking passersby to sign petitions.

In 2012, a protest erupted over new legislation against online piracy being passed into US law, which many argued fell to heavily into the realm of censorship. The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect IP Act (PIPA) were put forward as a way to curb online piracy and halt infringements on intellectual property yet the tough sanctions they proposed would mean that legal sites that had a section promoting the distribution of illegal material could face having their entire domain 'blacklisted' as opposed to simply being required to remove infringing content.

A protest was instigated by activists before organisations like Reddit and the english version of Wikipedia caught on and joined in by 'blacking out' the internert, blocking access to their content completely or only provided limited access to users. Google, Mozilla and Flickr also joined the protest and a number of street marches were held throughout the US to protest the laws. According to Wikipedia ''...3 million people emailed Congress to express opposition to the bills, more than 1 million messages were sent to Congress through the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a petition at Google recorded over 4.5 million signatures, Twitter recorded at least 2.4 million SOPA-related tweets, and lawmakers collected more than 14 million names...who contacted them to protest the bills.'' Though the flashy web black outs were what drew the most attention (and probably caused such a large number of people to protest), it is the individual activists who kicked off the campaign who have been credited with its success, with Forbes stating: ''...it was the users who urged and sometimes pressured technology companies to oppose the bills, not the other way around. While the big companies eventually came on board, the push for them to do so came largely from activists using social networking and social news sites, including Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr and Reddit, to build momentum and exert leverage, sometimes on the very companies whose tools they were using.'' The campaign, in part, has been credited with the proposed laws being reviewed and, for the moment, shelved.

Beyond getting the message out there, digital activism allows anyone with access to the digital world a platform to make their case and call for change and it can be particularly beneficial to those who are often silenced or have no vehicle for their message. Writing about the blurring of offline and online activism that occurred in the US following the shooting of African American teenager Michael Brown, founder and director of the Meta-Activism Project, Mary Joyce, stated ''...just like any other kind of activism, digital activism is only necessary when conventional methods of addressing injustice fail. “[I]nternet campaigns calling for justice” are only necessary for those whom the existing system does not serve.''

In April 2014, Boko Haram terrorists kidnapped more than 300 girls from a school in northern Nigeria. Some 50 girls managed to escape but 276 remained captured prompting an international outcry that was largely funnelled into a social media campaign to lobby governments to intervene. The topic #BringBackOurGirls went viral within a week, with people like activist Malala Yousafzai and US First Lady, Michelle Obama, tweeting their support. The rapid fire rate that the hashtag #BringBack OurGirls shot across the internet helped galvanise public support for the families of the girls while the case drew attention from the international media and heads of state offered to help Nigeria find and bring back the missing girls.

Where digital activism enjoys the biggest success however, is when it is used as a complementary tool to offline action or is used as the introductory method to encourage people to engage in offline action. One of the other key attributes of digital activism is that it is, for the large part, a non-violent form of protest. Acts of cyber crime are certainly committed under the guise of 'digital activism' (for example, cases of cyberterrorism, malicious hacking and extreme cyber bullying of a company or organisation) however, according to a study by the University of Washington, these make up around two to three percent of total digital activism cases.

Reduced to a Hashtag: Clicktivism and the Threat of Too Many Messages

Generally speaking, clicking like on someone's Facebook post or retweeting a trending hashtag on Twitter requires less effort and less forethought than signing (or setting up) a petition or joining in a demonstration on the streets. Because of this, digital activism has come under fire with some arguing that much of the online engagement in issues is too reductive and passive, defining this new era of activism as 'clicktivism', 'slacktivism' and 'armchair activism'.